The frame is perhaps the most common architectural optic device. It is an opening or a window of any size, proportion, position, or shape. The frame affects light effect by way of its edges and position with respect to the source of light and receiving surface. While a frame may be completely open, it does often hold a window that acts as a thermal barrier and weather barrier. It is important that the transparent surface, glass or otherwise, is as planar as possible, such that the trajectory of the light that passes through it is affected only by the uniform refraction that occurs as light enters and exits the medium.

Frames can exist as a single opening or as an array of openings and can exist in a number of orientations, producing a great variety of light effects. When the frame occupies an entire, exterior-facing wall of a room, it produces a neutral image. The interaction of surface edge and light produces the simple image, and textural light and a secondary source can also be produced when light and surface are brought into proximity to one another in the adjacent and opposite orientations respectively. Due to the reflectivity of the transparent medium, light that is not transmitted produces a visible but faint specular image on the medium’s surface.

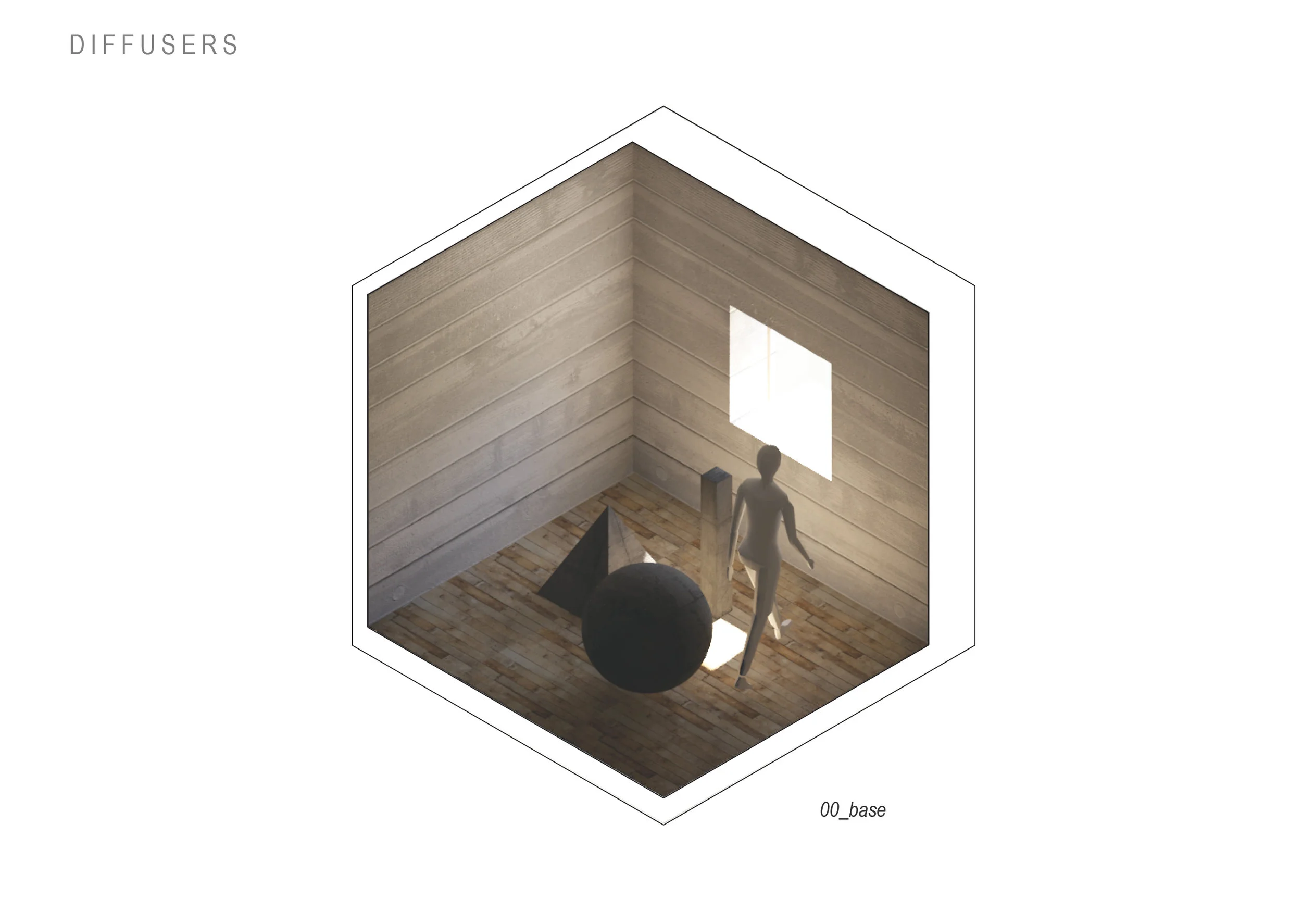

Sample Series of parameters applied in sequence to the base optic device